Bungling the Past

December 01, 2020

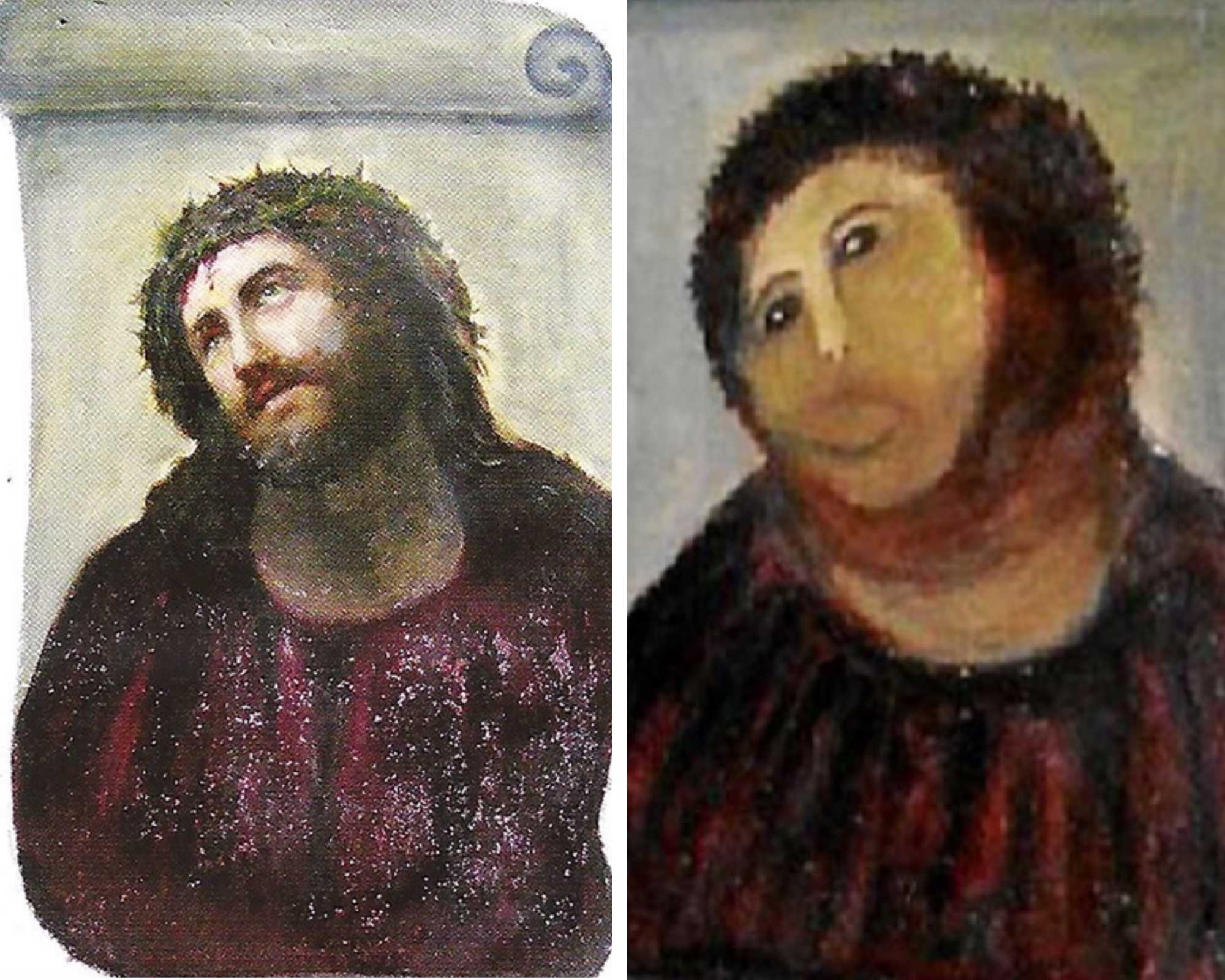

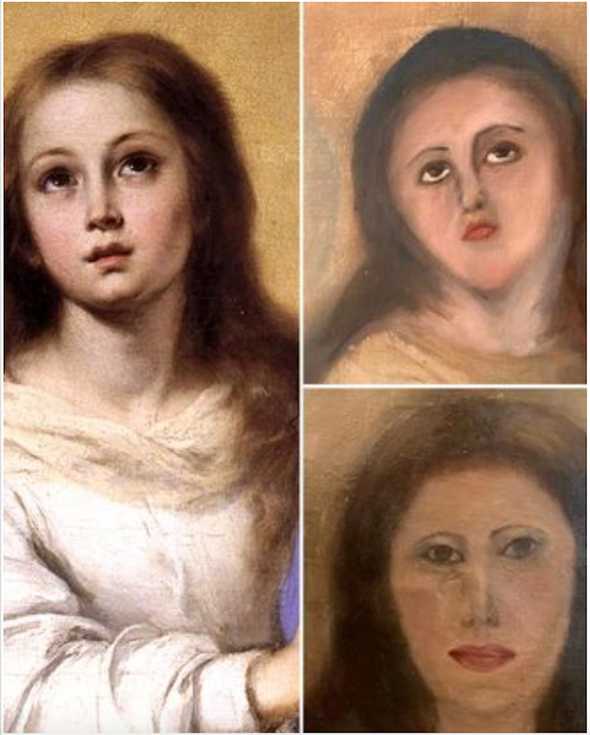

(above) A private collector’s copy of Bartolomé Esteban Murillio’s The Immaculate Conception of El Escorial after it was restored by a furniture restorer! (main image) Ecce Homo (Behold the Man) by Elias Garcia Martinez in Santuaruo de la Misericordia shrine in Borja, Spain. Right: Cecilia Gimenez’s disastrous restoration now nicknamed The Potato Jesus or Ecce Mono (Behold the Monkey)

Disasters in the form of talentless restorers and ignorant museum staff stalk museums and art galleries of the world. Humans have itchy hands and the gap between conservation and restoration is murky. Many restorations make one sigh with incomprehension. In China, Buddha images are the prime victims of devout bodgers. In Anyue County, southwest China, a millennia-old Buddha statue was brightly repainted in August 2018. The crime captured on a YouTube video.

The most notorious case of a botched cleaning was the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel at the Vatican, in the 1980s, under the supervision of Fabrizio Mancinelli, director of the Byzantium, medieval, and modern arts of the Vatican museums. Work on the ceiling was completed on 8 April 1989, and once the Last Judgement had been restored, Pope John Paul II inaugurated the revelation. His Holiness was well pleased, they said. His reaction proved that popes are no art connoisseurs. Or else he was careful not to unleash a storm given the obvious disaster inflicted on the frescoes. A fierce battle broke out. Historians blasted Gianluigi Colalucci (Chief Restorer for the Vatican) and his team. Though they had based their approach on the guidelines established, they obviously missed the most basic thing: Michelangelo might have used two fresco techniques, first applying colours on wet plaster, and then upper dark washes for shadows to enhance details, perspective, and mood on dry plaster. It is hard to believe the idea did not cross their minds. The result is a colourful, “charming” to the eye, profusion of damaged images. Some eyes are missing, draperies ironed out, foreshortening flattened, shadows evaporated, architectural detailing eliminated. Giorgio Vasary, a friend of Michelangelo, would have been pleased with the result though. He had lamented: “In seeking to show the emotions and passions of the soul, and in seeking this end alone, he (Michelangelo) has neglected charming colours.”

The culprit was the solvent AB57 that the Colalucci team used to give the ceiling a thorough cleaning! According to the American painter and historian Richard Serrin, “AB57 was developed for the cleaning of marble statues to remove the atmospheric grime that had accumulated on and penetrated into the pores of the surface. It is entirely unsuited for cleaning frescoes.”

Another controversial restoration involved Silvio Berlusconi who decided to add a shield, two hands and a penis to the antique Roman statue of Venus and Mars that adorned his office; he deemed it incomplete. The piece belongs to the Baths of Diocletian Museum in Rome. The penis was re-carved and fixed on with magnets, and so were the shield and the hands – pretty clever, Silvio!

Spain has had its share of awful restorations. The one in Borja by Cecilia Giménez takes the cake. In 2012, the octogenarian felt bad about the flaking face of Christ (Ecce Homo, Behold the Man) painted by the Zaragozan art teacher Elías García Martínez in 1930. She decided to act; the priest blessed her endeavour. Without the slightest hesitation she daubed patches of colours that she planned to refine with brushstrokes. Unfortunately, she had to go on a trip and left the job standing. The villagers were very upset, until they learnt that the author of the disaster was the devout Cecilia. Nevertheless, the outcome was beneficial for the sleepy community tucked in the foothills of the Sierra de Moncayo in north-eastern Spain. Suddenly, its economy boomed. The first year, 45,824 visitors stopped by to look at the Potato Jesus,or Ecce Mono (Behold The Monkey) as the portrait got nicknamed. The attraction still draws 16,000 curious yearly. And Cecilia regained the 17 pounds she had lost due to stress heaped on her by her national notoriety.

In Valencia, a copy of 17th century Bartolomé Esteban Murillo’s Immaculate Conception of El Escorial, said to be also by the Sevillian master, was disfigured by the furniture restorer engaged to clean it. The low estimate of US$1,200 should have alerted the owner. Right there, the effluvium of disaster hits you full blast before work begins: the varnish remover used dissolved the delicate layers of oil paints. After two reconstruction attempts, the damage was declared irreversible. The culprits received ‘administrative sentences’.

Paris’ Louvre Museum has its shares of bungled restorations, the better-known are Leonardo Da Vinci’s portrait of Saint John the Baptist, and The Virgin and Child with Saint Ann. Cleaning a Da Vinci is a serious mistake from the start, because the sfumato, the blurry effect, used by the artist is immediately affected. The master did not intend his figures to be bright in the first place. Apparently, the Louvre stopped fiddling with the Saint John the Baptist from fear of messing up the painting. The same did not happen with the second work though it was submitted to the approval of the International Committee of 20 experts, including those from the Louvre and London’s National Gallery. The French accused the British and the British accused the French. The fact remains: the painting is much too bright, details are lost and the face of the Virgin is altered. According to the Louvre, the National Gallery’s representatives, Larry Keith and Luke Syson, were adamant about there being no danger whatsoever to deep-cleaning the 500-year-old masterpiece.

Leonardo Da Vinci’s portrait of Saint John the Baptist – before, (left) and after an attempted restoration

Ségolène Bergeon Langle, director of conservation for all of France’s national museums and the authority in the science of restoring paintings, protested and resigned. Jean-Pierre Cuzin, eminent specialist at the Louvre did likewise. Michael Dalley, director of ArtWatch UK, criticised the National Gallery for its over-cleaning mania, in a bid to create a buzz and attract visitors. Both museums refused to comment. The truth of the matter remains hidden with many other secrets in the files of these famed institutions.

In 2001, Carlo Pedretti, the Da Vinci expert, announced the discovery of a Leonardo drawing: Orpheus being attacked by the Furies, in the collection of Stephano Della Bella. The excitement was brief. Restorers moistened the sheet of paper with water and alcohol. All the ink melted. What was left? A blank page.

The cherry on the banana split is King Tut’s beard. In August 2014, Cairo Museum employees managed to snap off the beard of the magnificent funerary mask during while dusting. The accident occurred in the gallery during museum hours. They quickly glued it back on with industrial epoxy but scratched the royal chin while removing the excess glue and got busted.

Where to see the art: Louvre Museum; Sistine Chapel; Church of Borja, Zaragoza, Spain; Grand Egyptian Museum.

Must-see: Sistine Chapel; Virgin and Child with St. Ann; Potato Jesus; King Tut’s mask.